He produces brilliantly coloured whimsical statue like sculptures in papier mâché, which brought him international renown. He has exposed his works in some prestigious museums at the group and solo shows in Amsterdam, Anvers, Barcelona, Berlin, Cologne, Geneva, London, Rio de Janeiro, Washington DC. He appeared on the covers of several fine art magazines, and was invited to produce art for high-profile cover art for Peter Gabriel music. The Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington D.C. has acquired one of his sculptures for its permanent collection.

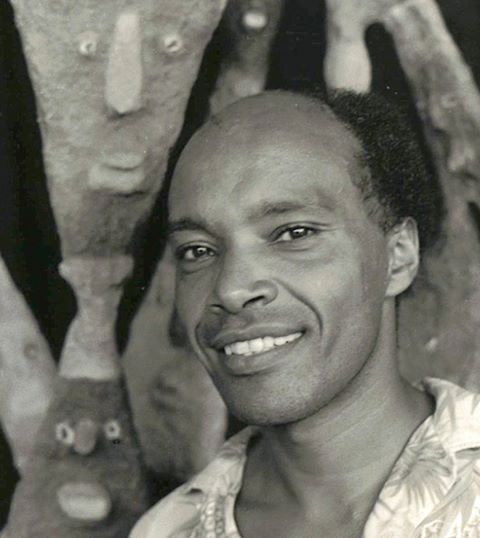

Few months ago he welcomed me at his home and basement studio in the 13th arrondissement where his works are displayed. I wanted find out what brought him here, why he chose to stay and what basing himself in Europe has done for his career. He speaks fluent yet heavily accented Amharic. Thoughtful, modest, lately turned 66, his is a long road toward recognition in this city of artists. No mean feat for someone whose artistic career came about somewhat unintentionally.

The second-born of three siblings, Mickaël was born in Dire Dawa. His father was a controller at Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Franco-Ethiopien (The Ethio-Djibouti Railway) who became custom officer in Ogaden. However, Mickaël was only three when his dad died, thus he did not have any of recollections of him. The toddler moved with his mother to Addis Ababa. He remembers growing up in those years in a loving family: mother, grandfather and grandmother in Qebena area. He passed his teenage years in Addis Ababa and studied at the French school, Lycee Gebre Mariam. After secondary studies at the Lycee, he obtained a scholarship to study in France. “I left Ethiopia in January 25, 1971. I passed my baccalauréat. At the time we were given grant, and I found myself in the science faculty because I had C in the bac and in Ethiopia there were no many choices. Those students who had C or D were generally not good in literary subjects, we were driven into science studies. Plus, I was good at mathematics. I was dutifully enrolled to study chemistry. However, after three years in university, I came to realize that it didn’t go with me. In 1975, I abandoned my study in physics and chemistry,” he says. He had then been mulling what to do with his life’s work. “I was not all that buff about being an artist,” said Mickaël, a slight and soft-spoken man, wearing a keffieh headscarf and cap. “It just happened to be something I did all the time.”

“I was in my student room. There was a shower and kitchen. The kitchen kind of annoyed me. I said to myself I had to do screen. So my first work of art was the screen. I painted at the deepest hours of night. It was great, imaginative and decorative. It was revelation for me and I said this is what I want to do. I bought a clay, I did small things in clay. It was then that I focused in papier mâché.”

This was In the 1970s, after a few of years of university study, he went to work small jobs to earn pocket money. His mother who used to work at Menelik Hospital died in 1974. “I turned thirty, unfortunately it was not a very good moment in France then. There was high petrol crisis in 1975, exactly at the same moment at the time of the Ethiopian revolution. Both unemployment and inflation rose. I managed to earn some money with small works,” he says.

It was here where Mickaël Bethe-Selassié was introduced to making papier mâché sculptures, made up of pieces of paper that are often reinforced with cloth or other materials and bound together with an adhesive paste. He kept on practicing the art and displaying his work in solo and group shows, including as part of a 1985 Galerie La Licorne, Paris, most of his works feature human figures. His homely, rough-surfaced papier-mâché, doused with color, evolved into considerably larger painted pieces.

One of the strongest moments in his artistic career was when he got his first chance to exhibit his works in his native Ethiopia in 1993 just after the downfall of the Derg regime. “I was contacted by the Director of the Alliance Française and I was elated. I asked him to give me one year to prepare. I put effort into the work. When it happened, it was special to me. It was special to get to show there. I never thought I would get this,” says the artist. The Ethiopian Television did a fifteen minutes program on him stressing his homecoming. “Addis was not moving like it is now yet the reception was warm. Viewers have strong responses, even though most of was from the ex-pat community. I made friends with artists, which gave me a reason to return on several occasions to reconnect. I feel a pull from Ethiopia, and there is some time soon when I will have to go back,” he says.

Mickaël Bethe-Selassié was one of the featured artists in Ethiopian Passages, a major exhibition of 10 contemporary visuals arts of the Ethiopian Diaspora, held at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art on from May-October 2003. The exhibition coincides with the 100th anniversary of U.S.-Ethiopia diplomatic relations and featured household names such Skunder Boghossian, Wosene Worke Kosrof, Julie Meheretu, Etiyé Dimma Poulsen, and Kebedech Tekalab. Mickaël particularly recalls his meeting with Skunder, who himself lived in Paris for nine years as both student and teacher at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière at the end of 1950. Skunder shared with him his reminiscences of the period at the time of war for Algerian independence from France, and his interaction with artists, sculptors, writers, intellectuals who were part of the Negritude movement and who would have a profound influence on his developing ideas. Skunder, unfortunately passed away few days later after their meeting.

Talking about his Parisian life, Mickaël says, “I do feel I’m part of the culture, of course. I have been living, making art, and showing some of it in Paris for 46 years. Here you find one of the most generous people around but they are always in hurry. It’s bit difficult to get into contact,”

“You have to go out from your community to make Parisian friends. As an artist I tend looking for like-minded people like me. But anyway I have never been a party guy type,” he adds. He said he was in relationship at some point, but finally opted for independence that he says allows him to live his life his way.

Has he become rich with his artwork? He laughs at the notion. “It is how many people back home thinks. There were times when I made a lot of money, where I have achieved commercial success. I invested it for the all the things I need, painting materials. There were times when I was broke. That is how it is.”

Mickaël is active on Facebook, sharing links to arts pieces and music videos. He reads, he listens to the radio. Otherwise, he leads a somewhat reclusive existence, keeping himself very much to himself. “It is not a problem for me. I go out sometimes to buy stuff that I need for my artwork. “

Mickaël has published a book in French in 2009 devoted to the life and work of his paternal uncle, Berhana-Marqos Walda-Tsadeq (1892-1943), who was civil servant, diplomat, government minister and missionary. “My father and my uncle had large age gaps, a difference of 24 years between their births. In fact, my uncle raised up my father. My uncle was a fascinating person. Born in Cherecher, Harergehe he attended the same Capucin Mission School where Ras Teferi Makonnen, later Haile Selassie was educated. He continued his education in the Ecole Imperial Menelik II in Addis Ababa, becoming one of the first students there, along with Blata Ayele Gebre, Gebre Igziabihir Francois. His career began in Dire Dawa, first in the railway, later director of the Post office and later became Ethiopian Charge d’Affaires in Turkey,” The book has many photographs of his early family.