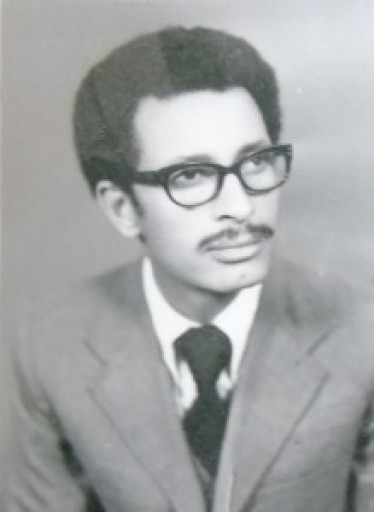

Mairegu Bezabih has served his country in various capacities for the past forty years. He had worked as special assignment reporter and feature writer for the Ethiopian Herald, department head of the English Features Desk of Radio Ethiopia, producer for “Balemuyaw Yinager” (Let the expert speak), a weekly television program, Editor-in-Chief of the quarterly magazine, Point Four, Editor-in-chief of weekly Amharic Yezaretu Ethiopia, the daily Addis Zemen, and Yekatit magazine. He also served as press counsellor of his country at the UN Mission in Geneva and at the Ethiopian Embassy in London. He was a columnist, editorial contributor and editorial board member for a private Amharic monthly magazine, Lisane Hizib, Deputy Chief of a European desk at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He is the founder and editor of the private English paper, the Daily Monitor. He has distinguished himself as a teacher of journalism and communication, teaching journalism, development communication and public relation courses at the Addis Ababa University and Unity University for over twenty years. Ato Mairegu has written a book on journalistic techniques as well as a history of print journalism in the country, Yegazetegnet Muya, Nidife Hasabu Ena Ategebaberu (The profession of Journalism, Its Theory and Practice). He has contributed articles, commentaries, reviews and historical studies to different publications and a piece on Ethiopia’s press history in Frank Barton’s book, The Press of Africa. He has written and edited work on a wide array of subjects related to reporting, press freedom, and public policy and he has appeared on many radio programs such as the Ethiopian Television, Radio Free Europe in Paris, BBC Bush House in London, Ethiopian Broadcasting Service (EBS) and Voice of America.

As a journalist, Mairegu has been instrumental in opposing government attempts to curb media freedoms through statutory regulation and secrecy legislation. When the current government introduced the press law in 1992, Mairegu was one of the few people who argued against some of the articles which he found might curtail and limit press freedom rather than enhance it.

Regarding the current state of journalism, Mairegu is of the opinion that it leaves much to be desired. “There is a problem with presenting news in a way that is accurate and factual. One reason being that news items are passed around among the papers without proper investigation of their accuracy and the appropriate editing. Follow-up is a very important task in journalism because most news items cannot be complete at first instance reporting. Most journalists lack the skill or the motivation to further investigate some happenings which could be of much interest to the public. Facts get mixed up, names get wrong. Most of those who are in the trade don’t have the proper training that the job requires. Most of the journalists who are now in the trade come to the profession with the experiences they had in mini media school. The ground is not propitious for journalism which is sober and highly responsible,” he says.

Mairegu was born in August 1938 in Korrem, Wag Awraja, in the former Wollo province, which he describes as the land of the Agew and Amhara. His father, Fitawrari Bezabih Yimam, was a patriot who died during the Italian occupation. His father’s younger brother Dejazmatch Hailu Kebede, who was posthumously appointed lieutenant general by Emperor Haile Selassie was a great heroic patriot who tried to liberate Sekota, the capital of Wag from the Italian occupation. He was killed in the war that ensued.

Mairegu’s mother comes from the same area, Wag. She was a housewife, a very religious type, he says. She was extremely fond of recounting her family history and lineage, which trait has passed on to him. Mairegu attended Atse Yohannes IV Elementary School in Mekele town and continued at Kusquam, Kokebe Tsibah and Asfaw Wosen schools in Addis Ababa. He later enrolled in the General Wingate School in Addis Ababa where he completed his studies in 1957. Mairegu says Wingate in those days was rather an elite school- a kind of Eaton of Ethiopia. “My years in Wingate were the most formative years in my life. It was in Wingate that I learnt about the history of this great country, Ethiopia, about our great emperors such as Tewdros, Yohannes, Menelik, and Haile Selassie,” he once wrote in the school’s publication.

At Wingate School he had an Amharic teacher who was influential to his future journalism and writing career. The teacher named Kifle Worku took a particular interest in encouraging him and his classmates, and through him he developed love of Amharic literature. “He talked about literature with great passion. It was contagious and inspiring. He convinced me of the great power of the Amharic language and who instilled in me tremendous love for Amharic literature, poetry, prose and drama,” he says. (Kifle later became Vice Minister before he died in a suspicious circumstance during the Derg.)

Mairegu also recalls his English literature teacher, Mr. Michael Halsted, who used to read Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in class. “He used to make us feel and live as contemporaries of ancient Romans.” As the teacher made him recite the words of Caesar, he remembers how he felt being a Caesar himself.

One of Mairegu’s year mates at Wingate who was later to become an eminent figure and his boss, was Baalu Girma. “Baalu was interested in music. I remember when there were recreational events on weekends, he used to sing his favourite French song, C’est si bon. Next opportunity for us to meet was while we were both working at the Ministry of Information. He started working as an editor for the then weekly, Yezareitu Ethiopia. Later he became state Minster, known then as Permanent Secretary, when I became an editor of Addis Zemen,” he says.

Another school mate, Tamiru Feyissa, was later to be known in the 1960’s student movements for his poem, “Dehaw Yinageral” (The poor man speaks out), a poem depicting the miserable life of the poor. At Wingate, Mairegu also formed a warm continuing friendship with Mengistu Hailemariam Araya, who went on to enjoy a distinguished career as presiding judge and later became Mairegu’s lawyer when he was put into prison.

After completing his high school education, Mairegu enrolled at the Extension Department of the then University College of Addis Ababa. He found the atmosphere at University College encouraging and inspiring. “We used to read and write a lot; we used to debate and compete with each other. “Thankfully, I received a very thorough liberal arts and literature background,” he says. He chose political science because he felt it has some kind of mysticism. He appreciates particularly Professor Schuldrinsky, Dr. Richard Pankhurst and Sven Rubenson. Pankhurst made a deep impression on Mairegu and got him interested in history. Pankhurst’s relationship with the students was very friendly, he said.

Rubenson was an enormous fan of Emperor Tewodros. “It was pleasing to see a foreign historian who devoted much of his time in researching on an African leader. He was so obsessed with Tewodros that even during his meal time and coffee breaks he used to incessantly talk about him. He later wrote a well-known book, “The Survival of Ethiopian Independence”. It was a real fixation and obsession,” he says.

Following his graduation, Mairegu travelled to study at Institute of Oriental Studies in Naples. However, it didn’t interest him. “It was mostly about Semitic languages, Arabic and Islamic disciplines. This doesn’t go with me,” he says. He instead joined the prestigious Johns Hopkins University, Bologna Chapter, where he studied advanced diplomacy and international relations. He found Bologna, a vibrant, exciting European city and he says his stay in Italy was pleasant. He never felt any racial prejudice.

How did he decide to become a journalist? In part, he says, it was accident. After his return from Italy with his masters in international relations, the employment that naturally occurred to him was to go the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and present his credentials in the hope of being employed, his expertise being Eastern Europe. He thought he would be of some use. “But the person who was in charge of recruiting personnel was not very enthusiastic about the job request”. While his qualification was desirable, they had no opening, he told him. Having his cherished dream dashed, he went to his hotel in a state of dejection. “The next day I had a surprise call from Shamble Atinafu, who was in charge of foreign publications department of Ministry of Information. He suggested that I could take up a post at the Ethiopian Herald. Since I had a master’s degree, they made me a special assignment reporter. I interviewed important personalities, including head of states during their official visit to Ethiopia.”

Even before going to Italy, Mairegu used to contribute articles to newspapers and magazines. On the following day, he headed to the Ministry of Information and sat down with Shamble Atinafu and the Colombia-graduate Tegegne Yeteshawork, whom he referred as “the giant journalist” to discuss about his employment. He was hired and to his surprise, he loved his new job. “I enjoyed it. It was quite exciting. I was young. There was also the glamor of it, you get invited to important events and embassy reception”.

Among the notable personalities he interviewed were the world renowned South African singer Miriam Makeba, the then freedom fighter Mandela and the Namibian freedom fighter who became the country’s first president. He interviewed Miriam Makeba, at the Hilton Hotel and he found her to be a fascinating personality. She used to hum while being interviewed.

Mairegu had a chance to interview many Ethiopian personalities over the years that became his friends. One was the late artist Maître artist Afewerk Tekle whom Mairegu interviewed for the first time in 1970 after the artist did an inaugural mural at St. Paul’s Hospital in 1970. (The large painting has a combination of religious imagery and a portrayal of the former Emperor Haile Selassie I, the hospital’s original patron.) “Afework lacked confidence with media people. When I was working for the Herald, the first article I wrote about him, he loved it. The painting was later criticised by the student movement for showing the Emperor as godly figure. But my article was positive.” Though some thought of the artist as pompous person but Mairegu doesn’t think it was a reasonable assessment. “You see, he went to England when he was young. He grew up among the aristocracy. Painters, poets and authors in Europe live like princes. He was also trying to do that here. He lived in a white stuccoed villa. He had a valet dressed gorgeously like those at Ras or the Ghion Hotel. His works were grand in scale. He has become rich with his works. Some thought he was pompous, arrogant, but my experience of Afework was that, he was, extremely meek, kind. He loved his country.”

While working for the Ethiopian Herald, Mairegu left for the United Kingdom for journalism training at the Thomson Foundation Editorial Studies Centre, Cardiff (South Wales). There he was attached to the newspaper, South Wales Eco where he wrote a number of articles, like one about Emperor’s Haile Selassie’s stay in Bath during his wartime exile.

With such a background and clear cut objectives, he came back enthusiastic about pursuing the profession of journalism. But that was to be somewhat thwarted as he was removed from his post in the Ethiopian Herald and put as head of public relations office for the Ministry of Information where he worked almost two years.

Then he joined the English service of Radio Ethiopia where he worked with colleagues like Teferi Wosen and Mussie Ayele. “We were writing feature stories and Leul-Seghed Kumsa would read it with his beautiful English accent. When Leul-Seghed wasn’t around, it would fall to us to read in his stead. Being an excellent reader that he was, he was naturally a hard act to follow and we naturally fell short”.

Then the revolution came, shortly after the ouster of Haile Selassie in 1974, Mairegu wrote for an English paper in London: “The journalists of Ethiopia, oppressed and frustrated from time immemorial-are biting their nails waiting to see what life without the Emperor will mean.’

‘The only consolation newsmen have in this wait-and-see period is that things can hardly be any worse than under the Emperor,’ he had written in the African Journalist, as quoted in Frank Barton’s The Press of Africa.

Watching the revolution unfold in its various directions, some positive, others negative, was a fascinating experience for Mairegu and his left-leaning friends and colleagues such as Asaminew Gebrewold, Berhanu Zerihun, Kefyale Mamo, and Azariya Kiros. Though he was later disillusioned with the military government, initially Mairegu was an enthusiastic supporter the Derg especially after the announcement of the land reform. He passionately supported the Ethiopian revolution that destroyed feudalism and liberated the peasantry from conditions of centuries -old servitude.

That was why he was appointed as editor-in-chief of Yezareitu Ethiopia in 1975 and promoted to edit Addis Zemen in 1977, tasked with providing wider coverage of the country in the papers.

During those years, he has earned a reputation for being a good editor and exacting standards of thorough reporting. Friends say Mairegu was good at hiring talent and supporting them in their youthful eagerness. His recruiting pitches also include contributors that would go on to become well-known writers, including Seyoum Wolde who later wrote in his memoir that the editor accorded him a lot of leeway by giving him a regular arts column.

However, he said the announcement of his appointment as editor of Addis Zemen put him at unease and he refused the offer, as he felt he ousted his predecessor, the venerated Berhanu Zerihun, editor since 1974. “I found it hard to accept the post because Berhanu was my friend. He was accused for being member of Meison. But Baalu Girma as permanent secretary of MOI told the night editor to put my name as acting editor, saying that this was the government decision, not mine.”

On the next day, his name appeared both in Yezareitu and Addis Zemen, as editor-in-chief of both papers which he said was “a special incident in life.”

After editing Addis Zemen for two years, he was appointed editor of the Amharic version Yekatit magazine in 1980. Yekatit was a monthly magazine, published in Amharic and English, which was devoted to political, economic, social, cultural and literary issues. The publication was some sort of a scholarly magazine to which many good writers had contributed articles- Asfaw Damte, Mamo Wudneh, Sebhat Gebre Egziabher, Seyoum Wolde, Tesfaye Gessesse, Mesfin Habtemariam.

Among Mairegu’s articles that were published in this magazine were a portrait of Tsegaye Gebre Medhin, entitled Ye Boda Abo Yesilet lidge (The promised son of Boda Abbo) that he did based on several interviews he has had with the renowned poet and playwright. The title alludes to the fact that Tsegaye’s mother may have promised her son to serve the Saint Abbo of Boda for having saved the family from the fire when their home was burnt down.

Asfaw Damte, who was later to become a prolific literary critic, started his literary work in Yekatit magazine. He recalls that for Miaregu to be appointed as an editor of a quarterly magazine coming from the busy daily paper, Addis Zemen, was mind-numbing. “He was a person working nonstop for the daily, Addis Zemen. He was a kind of person who gets energised by deadlines. I would say editing a quarterly magazine was a kind of punishment for him. At one point I said, why don’t you make it monthly? No, he said he was enjoying his holiday but I knew he didn’t mean it. One afternoon, he called me and he said, ‘Asfaw, I want you to contribute an article. My boss, whoever brought the idea to his head, also said “We should transform the magazine into a monthly publication. That was how I started my literary criticism columns which later continued in other newspapers and magazines. He was a really encouraging editor.”

An interesting episode occurred when Mairegu was editor of Yekatit. He decided to publish a letter from a reader asking “Why Comrade Mengistu Hailemariam was not in the habit of wearing traditional costume?”

“After receiving the letter, I brought up the issue to our editorial meeting. My colleagues, Mamo Woudineh, Shiferaw Mengesha, Sebhat Gebre Egzabher had divided opinions on whether it was safe to publish it or not. But finally we wanted to give it a test,” Mairegu says. “On the next editorial meeting led by Major Ghirma Yilma, Minister of Information, I was crucified. I was confronted with the question, “Was it with the intention of ridiculing and making fun of the president that you published the letter?”

The incident resulted in him being labelled as anti Derg and anti-revolutionary. For that he was fined 150 birr.

Mairegu had attended a course at the Yekatit Political School in 1979 for four months along with ambassadors, department heads and colonels. At the end of the training they were asked which sector they were interested to join. Taking advantage of the request, he readily joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a job which was dear to his heart. To his pleasant surprise, he was sent to the Ethiopian Mission to the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland as press councillor serving under Ambassador Kassa Kebede. He was later transferred to London where he served for four years under Teferra Haile-Selassie. He served for some twelve years in Geneva and London as press councillor, he served as Charge d’Affaire for his last year and half in the UK. It was also during this time that he availed himself of the opportunity to finish his master degree at Geneva’s Webster University in international relations. His thesis was entitled “The Image Distortion Campaign on the Third World Media in the West, Ethiopia case study”.

Among the publications he was involved with after EPRDF seized power was were the Monitor, a private English language newspaper which he edited and Lisane Hizib. Mairegu was member of the editorial board of the Lisane Hizib magazine (The Voice of the People) and he wrote a series of profiles on, such personalities as former Ambassador Yodit Imru, the famous aristocratic resistance leader Dejazmach Hailu Kebede, whose head severed by the Italian soldiers, another war hero General Jagama Kelo.

Mairegu expresses admiration for the “overwhelming majority of journalists” he has met both here and in Britain, speaking of their integrity and adherence to the professional standards. Mairegu is particularly warm about Berhanu Zerihun, the journalist, novelist, and playwright who died in April 1987. “I think he is one of the few intellectual journalists I have met in my intercourse with journalists in Ethiopia,” Mairegu pointed out. “He was well-read and left-leaning, as was fashionable in those days. He loved his country. He wasn’t interested in material wealth. Two of his brothers were very rich people. Amazingly, he never cared about material wealth. He was interested in literature. He red and he wrote continuously during his entire life,” Mairegu quipped. Mairegu also admired and wrote about another journalist, Assaminew Gebrewold, who he said was “the most popular Ethiopian journalist for a generation from the fifties to the sixties,” in his article that appeared in the Africa Journalist. “Assaminew had a subtle touch to his writing that enabled him to survive not only the pre-publication censorship, but also the post-publication scrutiny for ‘unexpressed negative ideas’. He achieved nationwide popularity among the educated classes, and though he was permanently in disfavour with the Emperor’s court and constantly fined for stepping out of line. He refused to compromise beyond a point that he thought he could live with,“ Mairegu wrote.

Mairegu spent a year and a half in jail in the current regime, on charges which the prosecutor was unable to prove. He was inwardly relived at the final outcome of his prison terms, for it was during this time he threw himself into writing his book on journalistic techniques, Yegazetegnet Tsinse Hassabuena Ategebaberu (Journalism, its Theory and Practice).

His main regret at the moment, Mairegu said, was that while he was keeping up with his many deadlines at the university— he didn’t have the energy to work on a memoir.