“I don’t have an interesting back story about why I became a journalist,” says Atnafseged Yilma. The experienced journalist, who began work as a cadet journalist at Voice of Ethiopia newspaper and Menen magazine at age 22, said his chosen career was the product of happenstance. “Having taught for ten months at the military school of office practice in Addis Ababa, I started asking around for another better-paying employment. A friend told me that there was a post in the Ethiopian Patriotic Association for a translating and reporting job. My training was chiefly in typing and office practice but I audaciously applied for the job and I sat down with eleven people for screening. Two of us were selected for the final oral interview. Though the other one had more experience, they took me because I settled for lower pay than he proposed,” the old-timer journalist and author recounts, when I met him at his villa in Gerji area recently. He is a genial interviewee and with his expressive eyes, flashing with intensity, draws people in, as does his warm smile and congenial nature. I could not fail to be impressed by his eloquent mastery of the Amharic language throughout the interview.

As he stumbled into journalism by accident, Atnafseged worked hard to master his craft and has managed, through the diligent application, to become a well-reputed journalist. Now 79 and still practicing the craft and maintaining a writing career, Atnafseged has authored four Amharic books titled “Recompense”, “The Riots of Animals and the Conference of Men” “The Rise and Fall of Abeto Iyasu” and “Secrets of My Life.” “The Rise and Fall Abeto Iyasu” has particularly proved successful; the book has not only been acclaimed by critics but has sold well. The book was praised for presenting the history of his nation from an Ethiopian point of view and a true portrait of the Lij Iyasu, the ill-fated grandson of Emperor Menilek, who though groomed to succeed his grandfather, was never crowned because of his rather unregally glamorous and wayward life. Atnafseged’s mastery of Amharic is revealed in a refined language which has made his books popular. He is putting the finishing touches on another book of historical interest, Ras Abebe Aregay.

Atnafseged was born in the town of Ticho, in the former Arsi province. His parents were landlords owning large plots of land. When his father died, his mother put the six years of age in the care of her grandfather who was head of the army ammunition storage depot known as Barud Bet in a Guguma village close to Shashemene, former Sidamo province.

“Originally hailing from Gondar, they settled in the area during the reign of Menelik II. My great-grandfather, Fitawrari Workneh was part of the Ethiopian forces on the southern front led by Ras Desta Damtew, governor of Sidamo, against the invading Italian army in 1935. The bold offensive was thwarted at the battle of Genale, which resulted in the massacre of Ethiopians. Fitawrari Workneh was captured in February 1937 along with Ras Damtew and other officials and summarily executed after the assassination attempt on Graziani,” he recalls.

Atnafseged then started schooling under the guidance of a church priest, who routinely beat students, was repelled and did not advance much. At the age of 14 or 15-year-old, he moved from Sidamo to Arsi. There he joined Ticho Kedamawi Haile Selassie Primary school and studied there until grade 8. He recalls walking 10km to school every day, carrying his school books. “When I had to walk to school, I had to be on guard against hyenas who happened to stray at dawn after the pack left in a field which they frequented. I once had a close call with such a hyena. I managed to escape by climbing on a tree branch. The other challenge was the ordeal of walking such a great distance to school. I would have some snacks for breakfast and would hit the road with a provision of Kolo, roasted grain in my pocket for lunch. I would go down to a nearby stream, drink a handful or two of water from the spring and clean my teeth with a wawate twig,” he recalls.

He did so well there that, after completing grade eight he was able to go on to Commercial College in Addis Ababa. To be in the city, which was constantly growing, was a big change for him. He loved the splendour of city life, the allure of the markets, the cacophony of the streets, the clustered houses teeming with children. He began studying secretarial science and accounting at the commercial college. “When I was completing grade 10, there was a conflict between Commercial College and the Addis Ababa Technical School students because of the shot sput sports event. I was a member of the team and we were sentenced to a month of hard labour, which I found unduly harsh. I quitted my high school education as a result,”

While wondering what to do next, he came to learn about a job opportunity at the Ministry of Defence’s Typing and Office Practice School, where he joined and worked there for ten months. He took a job as a reporter for Menen, work that instilled in him disciplines of journalism, that he practiced more than twenty years. After working as a translator and proof-reader, a typist at the bilingual publication, Menen, he was transferred to the Ye Ethiopia Dimits and Voice of Ethiopia, both dailies in Amharic and English. “The person responsible for my transfer was the late Ambassador Zewde Reta, the then general director of Menen magazine and Voice of Ethiopia, both operating under the National Patriotic Association. The Voice of Ethiopia was founded on the occasion of silver jubilee anniversary of Emperor Haile Selassie’s coronation as weekly and a few years later, it was elevated to a daily with separate Amharic and English editions under the editorship of Ayalew Woldeghiorgis and Yakob Woldemariam respectively,” he says.

(Atnafseged interviewing Professor Ephrem Isaac for the Voice of Ethiopia)

Accordingly, he set about applying himself to the task, news reporting, article writing, translation, proofreading. He was resolved to avail himself of the opportunity to learn from those who were ahead of him in the job.

“I was glad to have joined the profession of journalism which I have found to be enjoyable. Though I had little training, I fearlessly plunged into which demanded by its nature news mongering, research, maturity, objectivity, credibility, ethics, discipline, efficiency, and above all professionalism. Though my stay at Menen did not make of me much of a journalist, it had certainly aroused my interest for it,”

There he met many of the progressive writers and newspapermen of those days. He singles out for mention Bearya Gebre Selassie, whom he says was a good and tolerant editor.

The newspaper job suited Atnafseged’s inquisitive and fertile mind. It was an eventful period where young reporters were working hard against the odds such censures between the gulps of whiskey and the young Atnafseged’s curiosity and keen news sense produced hundreds of stories over the next decade. One particular event that he recalls happened while he was working for the Ye Ethiopia Dimts he wrote a news report exposing a shady practice of the then governor of Arsi province, Dejamatch Sahlu Defaye who unjustly forced the Arsi people to contribute, 80 birr per gasha land for the construction of Mojo-Aere road in Shoa Province, which was his birthplace. “As would be expected, the publication of the piece angered Dejazmatch Sahlu who then reported me to Prime Minister Akilulu Habtewold. The Prime Minister then ordered Dr. Minassie Haile, the Minister of Information, to administer appropriate punishment. Dr. Minassie called me to his office and to receive rebuke I was fined 100 birr from my salary, an order that he gave with a hint of apology in his voice,” he says. Dr. Minassie was sympathetic to the plight of journalists and Atnafesged was given back the 100 birr in the form of overtime payment.

On another occasion, Atnafseged was fined for an imprudent blunder that caused offense to the regime. The Somali government in its bid to realise its nightmare of establishing Greater Somalia, was trying to cede the Ogaden region from Ethiopia, by sending regular army and infiltrators. In the front page, there was a cartoon image under the caption, “one of the Somali expansionists” and there was a story about the Emperor giving a trophy to a leader of winning the sports team. The two captions mixed up and the news came out as “His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I awarding a trophy to one of the Somali expansionist”. Hell broke loose and his boss called him to tell him how angry he was and fined him, along with the editor-in-chief, Yacob Wolde-Mariam.

Another memory that stood out of those days was the friendships and a sense of camaraderie he enjoyed working with such colleagues as Paulos Gnogno, a self-taught journalist and urbanite, hailing from Dire Dawa. During the abortive coup d’état, Atnafseged says, press people led by Paulos organized a demonstration in support of the coup. “While we were marching to Ras Mekonen Bridge from Arat Kilo Square, we were stopped by a vehicle loaded with security people. Then Paulos who was always quick to come up with a way out ingeniously started shouting using a popular formula “Emperor Haile Selassie, come to the rescue of my soul.”

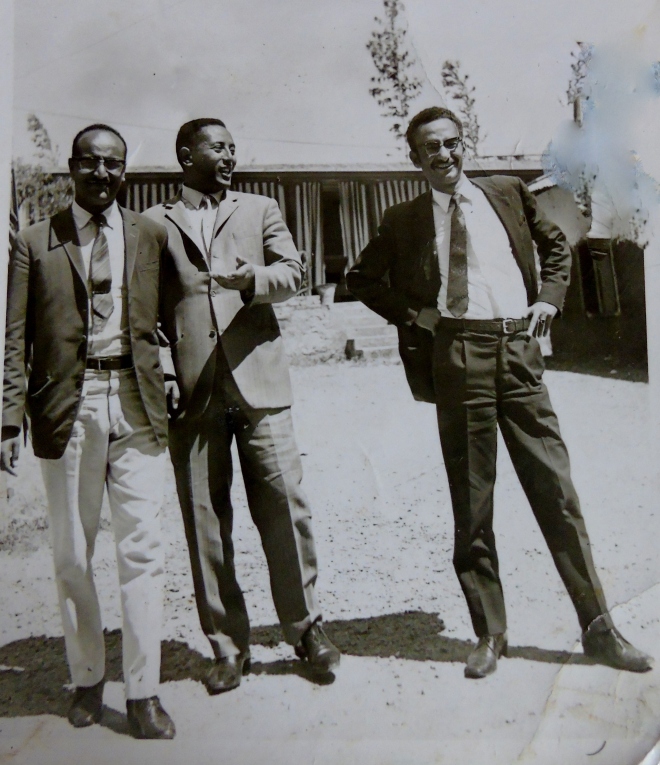

(Merse Hazen Abebe, Atnafseged Yilma, and Palous Gnogno)

After Voice was folded in 1973, Atnafseged was assigned to work as deputy editor-in-chief of Menen magazine, under the leadership of a journalist whom he said was his junior. He refused to work and he was unemployed for three months but he kept his salary. After three months, he was asked to participate in preparing a book, Selected Speeches of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I with another journalist Teshome Adera. “Though we were given a month, we managed to finish the task in fifteen days’ time,” he recalls. He was praised by his superiors and got a hefty bonus.

He then started working for the Amharic daily, Addis Zemen as a city desk editor, of which Baalu Girma was the principal editor from 1970-1973. Among his colleagues were senior journalists Kegazmatch Yared Woldemickael, Paulos Gnogno, Merse Hazen Abebe. It was a job that Atnafseged particularly remembers as demanding and fulfilling, spending a huge amount of time with colleagues in the field and newsroom, and overseeing the news operation which necessitated arriving home late often. It was a transition period when the feudal regime was in its twilight and when journalists enjoyed a relatively better, albeit brief, press freedom and enabling them to publish extensive investigative stories.

Atnafseged said he got along very well with Baalu Grima, for whom he was the best man in his wedding with Almaz Abera a few years ago. After the formation of Prime Minster Endalkachew cabinet, Baalu, he said, was criticized by the public for his editorial writing advising students and activists to “go slow”.

WhenKebede Anisa, editor-in-chief of the weekly Yezaretu Ethiopia, left for Wollo in 1973 to take a post as a general manager of development and planning, his post was filled by none other than Atnafesged. Though he liked the upgraded position, for him to be appointed as an editor of a weekly newspaper coming from the daily paper, Addis Zemen, was not an easy thing to get used to. All the same, with other two colleagues, sports reporter Abebe Wolde Tasdaik and culture and society writer Shiferaw Mengesha, the paper gained popularity, with circulation growing from 3,000 copies to 20,000 copies. Atnafseged calls this period the golden years of Ethiopian journalism, when the journalists were allowed the freedom to do what they wanted to write, discussing, debating and analysing issues of heated public concern such as land reform, the famine, drought and the future of the country, something that was not done before. However, that was not to last long, a year after the army took over the reign of government, and the newly-discovered freedom was crushed.

(Atnafseged and Berhanu Zerihun visiting the Space Museum, Moscow, behind Sputnik replica)

After a year Atnafseged was transferred to the Ethiopian News Agency, then located in Abune Petros area. He served there for three years, where at some point got into trouble when the names of military generals were misspelled. He left the news agency work, taking a job as a public relations officer at the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing, a post that he held until 1992, two years after the EPRDF took power.

After this, he joined a team of veteran journalists who embarked on launching a private press. In early 1992, Paulos Gongo launched a newspaper called Ruh together with his long-time colleague Kefale Mamo, Atnafseged joined the magazine as an advisor to the acting editor, Laekemariam Demisse, a diligent journalist, who took over the work after Paulos passed away suddenly. He also worked for another Amharic magazine Tobia, a magazine founded by Mulugeta Lule and his colleagues joining them as a guest writer.

The seasoned journalist who had accumulated a wealth of knowledge on the history of the country used the opportunity to write a series of articles on Abeto (Lij) Iyasu Michael that run on five issues under the pseudonym Aba Genbaw. He was later to build on the articles and develop them into a book, which came out two years ago. “After for ten years, the magazine run there was split in the editorial committee because of disagreement over ethnic representation. The disaffected group splintered to form another magazine called Lisane Hizib (Voice of the People) which I joined. I also did a series of articles on the famous patriot Ras Abebe, which I am working on to turn into a book. A regular contributor to Lisane Hizib of which he was an ordinary, and later honorary member, he wrote numerous articles and notes.

Atnafseged speaks in honor of colleagues whose achievements were especially meaningful to him. Of Mairegu Bezabih, he said, “What makes Mairegu stand out from among the other journalists is that he is well experienced, well educated in the profession. He started out as a reporter and eventually went on to become an editor. He strictly followed the basic five ‘Ws’ of journalism, mastering them and dutifully adhering to the principle. This enabled him to achieve clarity and accuracy and brevity, qualities which distinguished his work. He avoided verbosity, repetition. We tried to emulate him. Other journalists like Berhanu Zerihun didn’t care much for these principles,”

Mulugeta Lule was among the departed friends whom Atnafseged paid tribute, having worked with him for a number of years. When I asked him what he thinks of Mulugeta’s infamous book, Atifito Metfat, a book excoriating Mengistu Haile Mariam and his brutal ways, even though the author served loyally under the Derg regime. (There was a rumor that that Mulugeta wrote this book to curry favours with the current government.) “Mulugeta was a precipitous person. He was a loyalist to the Derg but he felt that had it not been for the blunders of the Derg, the system would not have been collapsed. I was cross with him because of the publication of the book but later when he gave me some justifications, I relented. I don’t think it was an attempt made to make peace with the EPRDF government. People may have their reasons to have such suspicions but deep at heart he was not the kind of person who wants to ingratiate himself with the regime,” Atnafseged defended him.

Of all his accomplishments, Atnafseged was most proud of his family. He and his wife, Almaz Sineghiorgis, an intense and vivacious woman, built a life surrounded by fun, friends, and family. (They have five children). They celebrated their ‘ 50th wedding anniversary two years ago. His marriage was not always a happy one and at one point they were almost separated, a story of which he narrated in length in his recent memoir.